The problem of out-of-school children is global. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), about 258 million children and youth are out of school. This total includes 59 million children of primary school age (6 to 11 years), 62 million adolescents of lower secondary school age (12 to 14 years), and 138 million youth of upper secondary school age (15 to 17 years) across the world.

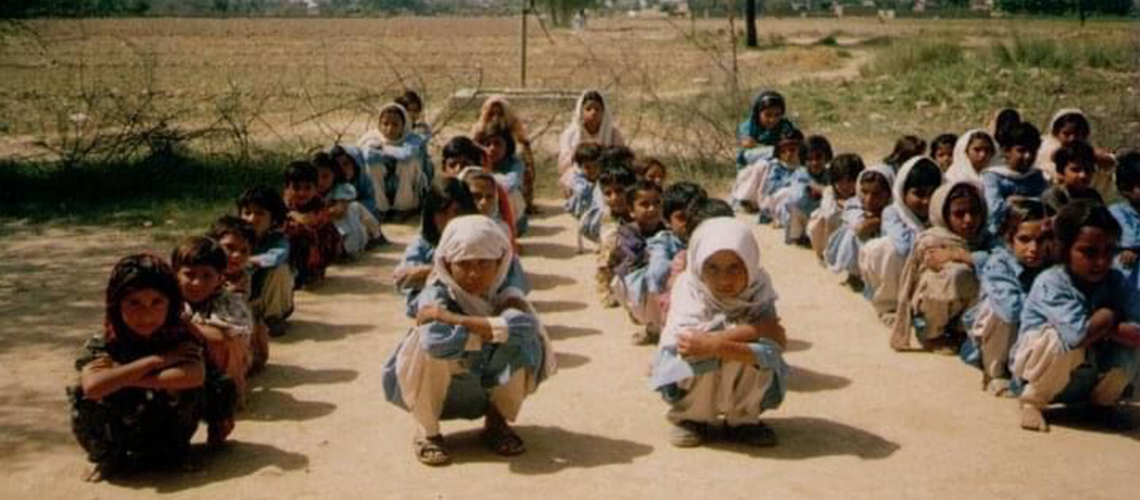

Pakistan has the second-largest number of primary school-age children out of school in the world after Nigeria. The country also has more out-of-school children, adolescents, and youth than any other country in South Asia. Currently, 5.6 million primary, 5.4 million lower secondary, and 9.8 million upper secondary school-age children are out of school in Pakistan.

On 25 September 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted an agenda for 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with 169 associated targets, aiming to achieve them by 2030. These goals and targets came into effect in January 2016. Pakistan is also a signatory to the SDGs. One of the targets of the fourth SDG is to ensure “that all girls and boys complete free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education by 2030.” However, the UIS reported that three years after the adoption of SDG 4, there had been no progress in reducing the global number of out-of-school children. The UIS further indicated that pupils dropping out of school has been a barrier to achieving universal primary and secondary education in the past.

Out-of-school children fall into two subcategories: “dropped out” and “never enrolled.” Evidence shows that most poor and developing countries have achieved more than a 90 percent enrolment rate. Despite progress in access, dropout remains a serious issue. These countries are unable to retain all children in school, and dropout rates continue to contribute to the global out-of-school population. It is clear that the world can only meet the SDG 4 targets if all children stay in school and complete equitable and high-quality primary and secondary education. Generally, dropout refers to children who enrol but do not complete compulsory schooling before they reach the legal school-leaving age.

Pakistan is a lower-middle-income South Asian country with a population of over 207 million, approximately two-thirds of whom live in rural areas. The overall gross primary school enrolment ratio is 94.33 percent; however, retention remains a major challenge. The overall survival rate to Grade V in primary education is 63 percent. For Classes I–VIII, the survival rate at national level is 48 percent for males and 43 percent for females. This rate declines further to 39 percent for males and 34 percent for females by Class X. This means that of all students who enter Class I, 61 percent of boys and 66 percent of girls drop out of school before reaching Class X.

If we consider exam failure among the remaining students at Classes IX–X, the number who ultimately complete secondary education becomes even smaller. For illustration, we examine Class IX annual examination results over the last five years at the Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education (BISE) Gujranwala, the largest educational board in Punjab. It includes six districts: Gujranwala, Gujrat, Hafizabad, Mandi Bahauddin, Narowal, and Sialkot. In 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019, only 40.58%, 54.01%, 52.84%, 54.51%, and 52.78% of the total candidates appearing in Class IX annual examinations passed, respectively. The average pass rate for the past five years at BISE Gujranwala is 51 percent. Among all provinces, only Punjab shows relatively better survival rates.

If we look at the percentage of students who successfully complete the secondary board examination at national level, we may conclude that out of all children enrolled in Class I, only about 30 percent graduate from high school after ten years of schooling, while the remaining 70 percent either drop out or fail during Classes IX–X. This is probably one of the highest school dropout rates in the world.

For a moment, if we set aside the notion of “equitable and quality primary and secondary education,” as stated in the SDGs, and focus on the constitutional responsibility of the Government of Pakistan to provide free and compulsory education for all children aged 5 to 16, it becomes evident that high dropout rates are a major barrier to achieving SDG education targets in Pakistan.

After a decade of independence, Pakistan formally introduced and implemented seven Five-Year Plans and five main national education policies to encourage socioeconomic and educational development. The focus of the first two Five-Year Plans (1955–60 and 1960–65) was on increasing primary school enrolment. However, the problem of dropouts was first recognised in the Third Five-Year Plan (1965–70). Yet, even 56 years later, Pakistan has never introduced a comprehensive national dropout prevention policy. Some provincial interventions—particularly in Punjab—have been implemented, mostly as cash transfer programmes to retain students, but these have not significantly reduced dropout rates. It is now time to design an effective national dropout prevention policy to achieve SDG education targets by 2030.

National policy should focus on dropout prevention strategies rather than merely enrolment drives. Effective interventions require local analysis of problems and assessments of community-specific strategies at the point of service delivery. Therefore, I recommend a bottom-up policy approach to understand and address the problem of dropouts at the grassroots level.